Person-centered care is a current buzz word in health care. In one article, the core of person-centered care is described in this way: “patients are known as persons in context of their own social worlds, listened to, informed, respected, and involved in their care – and their wishes are honored (but not mindlessly enacted) during their health care journey.” In other words, health care is finally catching up to practices that have been at the core of social work for a long time. Huzzah!

I really don’t mean to be flippant or disrespectful. This focus on person-centered care is a good thing in my opinion and is not really new to health care either. There are articles in nursing journals, for example, about person-centered care as far back as the 1950s. But from my seat it’s still an interesting thing to watch unfold. I’m not by any means a neutral, unbiased observer, not only because of my perspective as a social worker, but because (full disclosure) I’m part of a research project funded by the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Initiative (PCORI). And measuring person-centered care and outcomes is, we are discovering, no easy task.

So I was interested to read the 2014 National Healthcare Quality & Disparities Report published by the Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ). One of the priorities of the National Quality Strategy developed as part of the Affordable Care Act is “person-centered care” defined as “ensuring that each person and family is engaged as partners in their care”. That means health providers need to communicate with patients about their health in meaningful ways, facilitate the patient’s involvement in their own care, and be able to spend the time with the patient that is needed to make these things happen.

The 2014 report includes some data around person-centered care that are interesting, even though they suggest to me that we’re not the only ones finding this measurement issue a challenge. Here’s a summary of some of these data for adults 65 and older (data are available for adults 18 and up as well as for children as reported by parents):

Among adults 65 and older who had a doctor’s office or clinic visit in the 12 months before the interview, 5% reported that their health provider did not:

- listen carefully to them,

- explain things clearly, or

- show respect for what they had to say.

Among those with a usual source of care:

- 4% reported health care providers did not ask them for help making treatment decisions, and

- 7% reported health providers did not spend enough time with them

At the same time:

- Ninety-five percent reported that health care providers explained and provided all treatment options.

It’s not immediately clear from the data how to reconcile these differences. There are data that suggest differences across racial/ethnic groups, by education, and other demographics that may help pull some of this apart, but that’s for another post. Overall, these data seem pretty positive.

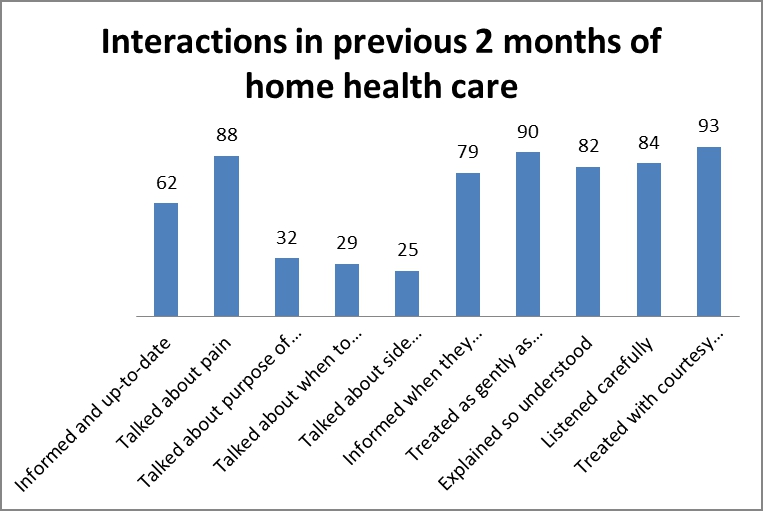

Most hospital patients had good communication with doctors and nurses defined as being treated with courtesy and respect, being listened to carefully, and having things explained clearly. The majority also had good communication about the medications they received in the hospital and about discharge information; however, 10% and 13% respectively did not. One goal of person-centered care is to help patients better manage their own care. Given that medications and post-discharge follow-up are points of difficulty that often lead to re-hospitalization, these are places where we have work to do.

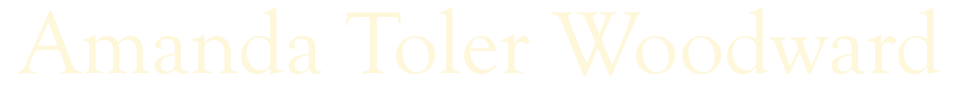

When they first started home health care, the majority of patients were told what care and services they would get and about how to set up their home so they could move around safely. They also had a conversation about their prescription and over-the-counter medications and were asked to show the home health provider all the prescription and over-the-counter medications they were taking (an important step to make sure you know about them all).

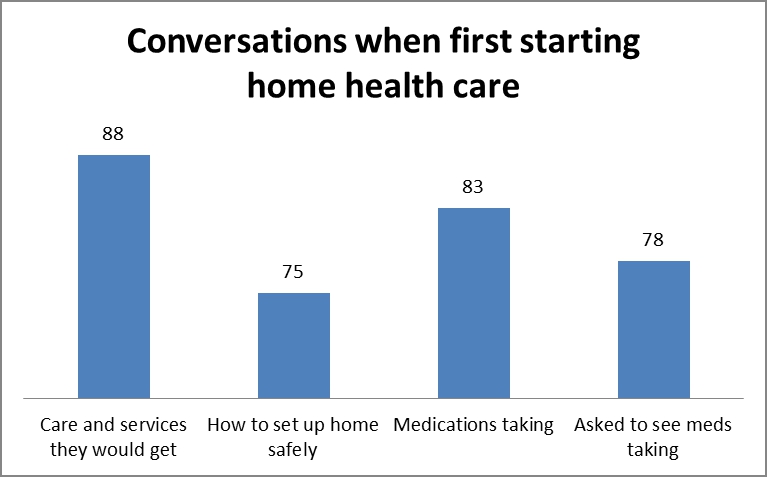

In the previous 2 months of home health care, the majority of patients felt that the home health providers were well informed and respectful, treating the patient gently, letting them know when they were going to visit, listening to them and treating them with courtesy.

In terms of involving the patient in their care, however, at least around medications, many fewer patients reported that the home health providers talked with them about the purpose of medications, when to take them, or the potential side effects. In addition, only a quarter (26%) said they got the help or advice they needed when they contacted their home health provider and the majority (93%) reported having some problems with the care they received.

Finally, among hospice patients, the experiences were positive with the majority being referred to hospice at the right time, the patients received the right amount of medicine for pain management, the right amount of help for feelings of anxiety or sadness, and care consistent with their stated end-of-life wishes.