Ageism is prevalent, even among social work students. This is impacting the number of social workers trained to work with older adults. But the good news is, this is something that can be addressed in the classroom and via practical training.

Ageism is prevalent, even among social work students. This is impacting the number of social workers trained to work with older adults. But the good news is, this is something that can be addressed in the classroom and via practical training.

“I want to work with kids where I can have a real impact”. We hear this from students all too often.

The number of students interested in specializing in gerontology is declining. At the same time, we need more doctors, nurses, and social workers trained to work with the growing number of older adults. On a practical, I-need-to-find-a-job-when-I-graduate level, this doesn’t make a lot of sense. The number of aging-related jobs is on the rise and will continue to do so for the next few decades.

Even those who work in areas like child welfare or school social work are finding that older adults are increasingly part of the package. I’ve had students work with families in foster care where the kids are being parented by their grandparents or other aging relatives who are themselves dealing with planning for their long-term care. That’s not what these students envisioned when working with kids. The truth is, some specialized training in aging and working with older adults broadens your opportunities.

However, the ageist stereotypes that stop students from being interested in doing this work are a powerful force. Social work students say they don’t want to work with older adults because they’re afraid, they don’t want to deal with death, it’s depressing, and it’s emotional work. And yet many of these same students want to work in child welfare. How, I ask you, is that less emotional work? In fact, what area of social work is NOT emotional work? Emotional work is what we do whether we’re sitting face-to-face with individuals, organizing community members to take action, or testifying before Congress.

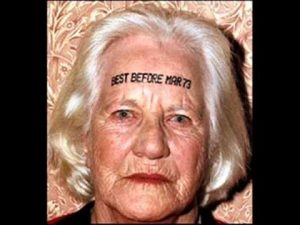

I don’t blame the students. Given the images we are regularly fed of frail older adults, who wouldn’t rather work with sweet little kids who still have their whole lives ahead of them? The potential to change a life seems so much greater with the young. Except, of course, when you work with kids you don’t work only with kids, you work with their parents. And you deal with poverty and racism and illness and dysfunctional social systems just like we do in every other area of social work practice.

And who says there isn’t equal potential to change the life of someone who’s old? And why is that change seen as less worthwhile?

If I just made social work sound horribly depressing, that’s definitely not my intent. My point is simply that all social work is hard work and the reasons I often hear for not wanting to work with older adults typically apply to all age groups. It’s just that we give kids a pass because we think they are cuter. Okay, maybe most of them actually are cuter, but cute in this case is also code for more rewarding or less difficult to work with or less depressing. And none of this is necessarily true.

The good news is that, for all of us, increasing knowledge about aging and having contact with all sorts of older adults can change attitudes. I’ve used several techniques to spur ah-ha moments from my own students.

Demonstrate that older is relative.

When I teach a class on mental health and aging, one of the first things I have students do is interview an older person. I purposely don’t specify what “older person” means so the students tend to take it literally and interview someone who is older than them. They return with interviews with people whose ages fall anywhere from 50 to 102. Since the students tend to vary in age and experience as well, these choices alone lead to interesting classroom discussions. What does it mean, for example, when your 23-year old classmate chooses someone your age (or even younger than you) to interview about what it’s like to be an older adult?

Suddenly, we’re talking about how language shapes perceptions. After all, my friend’s 4-year old nephew is an older person relative to his 3-year old friend at preschool. We’re all aging and that involves physiological, emotional, and psychological changes from birth to death. But for some reason, once we pass adolescence, we stop thinking about aging in terms of development and start thinking about it in terms of decline.

Expose that we hold ageist stereotypes even about the older adults we know best.

The interviews I give my students include questions about the experiences of aging, both good and bad, and ask what each subject is looking forward to and worrying about in regards to the future. Reports of contentment and plans for an active and busy future are common. Yes, there are concerns about losing independence or being a burden on their family, but frankly you don’t have to be on the other side of whatever “old” is to have those worries.

What’s striking, is that it doesn’t matter whether the students are interviewing their father, grandmother, an uncle, or their next door neighbor–they are always surprised by this positive outlook. One student went so far as to say (and I paraphrase) that she realized she hadn’t been thinking of the older adults in her life as actual people outside of their role as Grandma or Aunt Jane. She saw even the older adults she was closest to through the filter of stereotypes.

My ultimate goal as a faculty members is to increase the number of students who go into gerontological social work. My goal as a writer and educator is encourage all of us to think critically about the labels and language we use to talk about groups of people and to challenge the systems we’ve put in place to support them.

What little thing can you do today to challenge ageism?

Want these posts to come directly to your inbox? Enter your email in the subscribe box to the right (or at the bottom of the page on a mobile device).

As I write this, I’m sitting in rural Finland enjoying a lovely view of barley fields and peacefully grazing horses (and rain). As I write this, all hell is breaking out at home – again. Two more black men killed by police in as many days, violent protests – again.

As I write this, I’m sitting in rural Finland enjoying a lovely view of barley fields and peacefully grazing horses (and rain). As I write this, all hell is breaking out at home – again. Two more black men killed by police in as many days, violent protests – again.