Sometimes people make bad decisions. They overload high interest credit cards, skip rent payments, skip doses of medications to make the prescription last longer, quit a job, and refuse the help that is available to them. From the outside it can seem like they are dysfunctional or lazy or irresponsible.

But we don’t typically know the whole story. Maybe they quit their low-paying job because they have a child with special needs who requires full time care they can’t afford. Maybe they made too much for government help, but not enough to pay for care out of pocket. Maybe cable television is the only thing that keeps their child quiet for a little bit so they can get other things done. Maybe the only way to get help is to stand in long lines during working hours.

People don’t get help for a lot of reasons. A recent article by Lens et al examines this issue in relation to material hardship and presents the idea of survival fatigue.

Material hardship

Material hardship is the inability to meet basic needs. It’s hard to find a measure of how much material hardship there is in the United States (readers, if you know of such a thing, let me know). Lens et al found in previous work that 23% of New Yorkers were poor and 37% had at least one acute instance of material hardship. This includes low-wage workers as well as those relying on government support. Jobs alone are not the answer if they don’t pay enough to live on.

For many of these people, help is available from nonprofits, but they don’t ask for it. Stigma and knowledge of what is available are two common reasons. But these authors focus on another issue – how our ability to make good decisions is affected when we are living in scarcity.

Survival fatigue

There is some evidence that living in poverty creates cognitive overload which in turn can limit our ability to make decisions. Survival fatigue is the result of this. It is when we are so psychologically exhausted that we become paralyzed and unable to make good decisions which digs us into an even deeper hole. I imagine most of us have experienced some version of this at some point in our life. In this context, it’s a daily way of life because of the ongoing struggle to just make ends meet.

There is some evidence that living in poverty creates cognitive overload which in turn can limit our ability to make decisions. Survival fatigue is the result of this. It is when we are so psychologically exhausted that we become paralyzed and unable to make good decisions which digs us into an even deeper hole. I imagine most of us have experienced some version of this at some point in our life. In this context, it’s a daily way of life because of the ongoing struggle to just make ends meet.

Lens et al talked to 70 low-income people about whether or not they sought help from nonprofits. They found that some people use nonprofits a lot, others occasionally, and some never seek help. But the distinctions were more nuanced than users vs non-users. Among the users there were:

- The active help seekers – those who gathered information on all kinds of services and shared it with others;

- Sporadic users – those who forged a connection with a specific nonprofit and used their services regularly, but didn’t seek help from others;

- Selective users – those who sought help for a specific need, such as disability benefits for a child, but not for things like rent assistance or help with groceries even though they knew the help was available.

For those who did not seek help or did so only occasionally, the reasons were similar to those found in other research including stigma, knowledge of services, burdensome application processes, and other psychological (e.g., depression) and practical (e.g., transportation) barriers.

What they also found is that survival fatigue interacts with these barriers in a variety of ways.

- Stigma can exacerbate survival fatigue. Food pantries, for example, were seen as a symbol of the lowest you can fall, particularly among low wage workers. Buying food is one of the most basic things these workers feel they should be able to provide and the fact that food pantries often require standing in lines outside, sometimes for hours before they open, adds a sense of public shaming. For many, this is seen as rock bottom and reaching that financial low contributes to paralysis and an inability to act.

- Nonprofits are often less visible and less well known than government supports. Survival fatigue makes it hard for people to expend the extra energy needed to find these services.

- Once they find them, burdensome application processes make it hard for people to access them. This is particularly true for low wage workers who have to juggle work schedules and kids’ schedules with nonprofits’ working hours and long lines. Survival fatigue magnifies these difficulties.

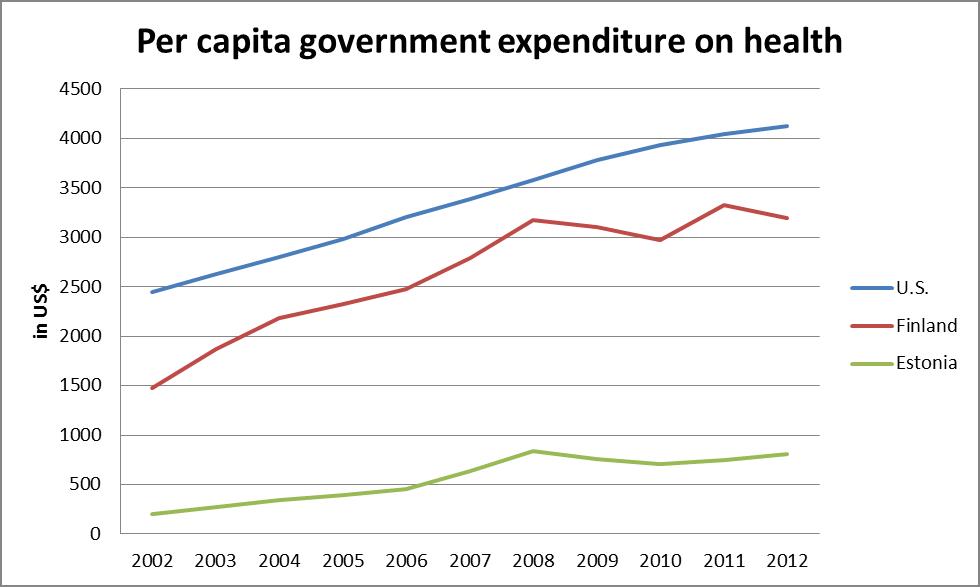

Lens et al paint a picture of people who are anything but lazy or irresponsible. These are folks who work hard and just don’t have an ounce left to give. While the authors give suggestions for how nonprofits can make it easier for people to access the services they provide there are larger systemic issues to work on here – jobs that pay a living wage, universal health care, and a safety net with fewer gaping holes being high up on the list.

In the meantime, if you need help with food, housing, utilities or other issues try http://www.211.org/ or call 211 at . . . well, 2-1-1.

Ai-Jen Poo is the director of the

Ai-Jen Poo is the director of the